Starting Delivery Site

Model Inputs \(\rightarrow\) Health System Parameters \(\rightarrow\) Starting Delivery Site

Overview

Women may deliver either at home or in a facility. Medical facilities are classified by the level of emergency obstetric care (EmOC) they can provide. Basic EmOC (BEmOC) is comprised of six signal functions which include administration of injectable antibiotics, oxytocics, and sedatives/anti-convulsants, performance of manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products, and assisted vaginal delivery. In addition to these six signal functions, comprehensive EmOC (CEmOC) offers blood transfusion, surgical capability, and management of shock.[1] The WHO recommends a minimum of 5 EmOC (combination of BEmOC and CEmOC) facilities per 500,000 population, where at least 1 is comprehensive.[1] Delivery sites are split into 5 categories in the model: Home, Home - Skilled Birth Attendant (SBA), non-EmOC, BEmOC, and CEmOC. The starting site determines what preventative care a woman may receive (if any), thus potentially reducing her risk of delivery complications, and influences the probabilities that a complication may be recognized, referred, and transported.

Data

Facility Delivery

We analyzed delivery site (home vs facility) from DHS data (variable m15) for 1,717,203 women in 75 countries from 261 surveys. We supplemented this with country-level data from the Global Health Observatory on births attended by skilled health personnel for 108 countries not available in the DHS data.[2] We use the data on skilled birth personnel as a proxy for facility delivery. We used the same priors for all subgroups in these (non-DHS) countries. From both sources of data we obtained estimates for 183 countries between 1990 and 2018. For “Home SBA”, we considered SBA as reported in DHS as a doctor or nurse/midwife. Overall, few women delivered at home with SBA (about 3.5% globally). We estimated the probability of SBA given home birth among 684,977 women in 75 countries from 257 DHS surveys. Due to lack of DHS data for high income countries we used the priors for upper middle income countries.

Facility Type

To estimate the distribution of EmOC facilities we undertook a targeted literature review, summarized here by continent.

Africa

- Angola: A 2019 report in focus provinces estimated that 50% of municipalities could provide BEmOC and 10% could provide CEmOC.[3]

- Benin: A study of services provided in 2002 found 26 CEmOC facilities and 19 BEmOC facilities, and that 72% of deliveries occurred in any facility while 13% occurred in EmOC facilities.[4]

- Burkina Faso: A comparison of two EmOC surveys in 2010 and 2014 found that 71.7% of births occurred in facilities and 3.4% occurred in CEmOC in 2010, and that 42.6% of births occurred in facilities and 4.5% occurred in CEmOC in 2014.[5]

- Burundi: A 2018 UNFPA document reported that there were 7 BEmOC and 23 and CEmOC facilities.[6]

- Cameroon: A 2000-2001 study in 5/10 provinces found 5 BEmOC and 21 CEmOC and estimated that 5.9% of births occurred in all facilities.[7]

- Chad: A study of services provided in 2002 found 24 CEmOC facilities and 7 BEmOC facilities and that 9% of deliveries occurred in any facility, with nearly all occurring in EmOC facilities (28153/29226).[4]

- Côte d’Ivoire: A 2000-2001 study in 16/46 districts found 104 BEmOC and 15 CEmOC facilities, and estimated 45.1% of deliveries occurred in all facilities and that 31.3% occurred in EmOC facilities.[7]

- DRC: A 2012 study in three provinces found that out of 266 facilities 5 were BEmOC and 4 were CEmOC, and estimated that 0.8% of births occurred in an EmOC facility, and that 25.4% occurred in any facility.[8]

- Ethiopia: A census of almost all health centers and hospitals in the country (795 facilities) in 2008 found that there were 58 CEmOC, 25 BEmOC, 712 ‘partially functioning’ or non-EmOC facilities.[9] The study estimated that 7% of expected births occurred in a facility, and 3% of births occurred in an EmOC facility.[9]

- Gabon: A needs assessment of services provided in 2001 found that of 77 facilities 11 were CEmOC and 5 were BEmOC.[10] 74% of births occurred in any facility, and 14.5% occurred in EmOC facilities.

- Gambia: A study of services provided in 2002 in 47 health facilities found that 4 were CEmOC and 8 were BEmOC, and that 30% of deliveries occurred in EmOC facilities.[10]

- Ghana: A nationwide EmOC needs assessment in 2010 found that 57.7% of expected births occurred in facilities, and 20.7% of births occurred in EmOC facilities.[11]

- Guinea: A national EmOC needs assessment was conducted in 2012, including all public, private, and faith-based health facilities that performed at least one delivery during the period of study. Out of 502 health facilities survey, 421 health centers were expected to perform BEmOC signal functions, but none was actually a fully functioning BEmOC facility due to low performance in terms of assisted vaginal delivery and neonatal resuscitation - all 15 EmOC facilities were CEmOC, and only 2 were in rural areas.[12]

- Guinea-Bissau: A nationwide survey of 107 health facilities in 2002 found that 3 were CEmOC and 11 were BEmOC, and that 29% of deliveries occurred in EmOC facilities.[10]

- Kenya: The 2010 Service Provision Assessment of 129 facilities offering delivery services found that 9% of facilities reported the ability to carry out BEmOC, and 7% reported the ability to carry out CEmOC.[13] A 2003 study in North-Eastern Province estimated that 8.8% of deliveries took place in EmOC facilities.[14]

- Malawi: A 2006 study of three districts in central Malawi found that 40.6% of deliveries took place in facilities, and that 22.5% occurred in EmOC facilities.[15]

- Mali: A study in 2001-2004 in two districts (Bougouni and Yanfolila) found that the proportion of births in EmOC facilities was 5-6% on average.[16]

- Mauritania: A 2000-2001 study of all facilities found 1 BEmOC and 7 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 35% of deliveries occurred in all facilities.[7]

- Morocco: A study of services provided in 2000-2002 of 510 government maternities and birthing centers found 137 BEmOC and 61 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 49.4% of birth occurred in all facilities, with 40.5% of births occurring in EmOC facilities.[17] Private hospitals were not surveyed however.

- Mozambique: A study of availability of EmOC facilities in Mozambique found that the institutional delivery rate at EmOC facilities increased from 17% in 2007 (57% all facilities) to 19% in 2012 (67% all facilities). Nationally there were 78 EmOC facilities (33 CEmOC) in 2007, and 67 EmOC facilities (32 CEmOC) in 2012.[18] A needs assessment in Sofala province in 2000 found 1 BEmOC and 4 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 34.2% of births occurred in any facility, and 12% occurred in EmOC facilities.[19]

- Namibia: The 2016 national emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessment estimated that 94% of births occurred in hospitals expected to provide CEmOC, however, only 28.3% of them occurred in fully functional EmOC facilities. The report estimated that in 2016 95.7% of births occurred in health facilities - 94% in hospitals, 5% at health centers, and 1% in clinics. In 2005, 70.9% of births occurred in health facilities, of which 95% occurred in hospitals, with 23% of all births delivering in EmOC facilities.[20]

- Niger: A study of services provided in 2000 found 54 BEmOC facilities and 22 CEmOC facilities, and that 11% of deliveries occurred in any facility - however, the number of deliveries in EmOC facilities was not available.[21]

- Nigeria: A study of facilities in Bauchi State between 2012 and 2015 found that BEmOC facilities increased from 3/59 to 8/59, and CEmOC increased from 3/59 to 13/59, and that facility deliveries increased from 28,455 to 35,818, of which 8,483 and 19,383 deliveries were in EmOC facilities, an increase of 30% to 55% of facility deliveries.[22] Another study in Kwara state in 2013 found that 38.7% of all deliveries took place in health facilities, and 13.6% of all births occurred at EmOC facilities.[23]

- Rwanda: A study in 2004 in 4 districts estimated that 7.2% of deliveries occurred in EmOC facilities.[14]

- Senegal: A national needs assessment of 172 facilities in 2001 found 5 BEmOC and 33 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 28.6% of deliveries occurred in all facilities surveyed, and 9.7% occurred in EmOC facilities.[19]

- Sierra Leone: Sierra Leone is divided in 13 districts, and each district has one healthcare facility designated to provided CEmOC and five or six designated to provide BEmOC. In total, 13 facilities were designed to provided CEmOC and 67 facilities were designated to provide BEmOC.[24] A previous study in 2008 found that 9.6% of births took place in a health facility, and 2.3% of births occurred in an EmOC facility.[25]

- South Sudan: A study in 2003 found that the proportion of deliveries in EmOC facilities was 0.6% in Yambio and 1.5% in Rumbek.[14]

- Tanzania: A health facility survey in Zanzibar in 2012 found that 47% of all births occurred in EmOC health facilities, and of 79 sampled facilities 9% were CEmOC, 7.6% were BEmOC, 27.9% were ‘partially BEmOC’, and 55.7% were non-EmOC.[26] A needs assessment for 1999-2000 in 2 districts in Mwanza Region estimated that 43% of births occurred in a facility and that 14% occurred in EmOC facilities.[21]

- Uganda: A study in 2003 estimated that nationally 5% of deliveries occurred in EmOC facilities.[14]

Asia

- Afghanistan: An assessment in secure areas of Afghanistan in late 2009 to early 2010 found that 53 of the 78 facilities (68%) performed all basic EmOC signal functions, and 44 of the 78 (56%) performed all comprehensive EmOC signal functions.[27]

- Bangladesh: A study of a sample of 14 public and private health facilities in rural northwest Bangladesh in October 2011-January 2012 found that 3 offered BEmOC and 11 offered CEmOC. All private clinics (7/7) provided CEmOC, while 4/7 public facilities provided CEmOC, however, only 3,217 deliveries occurred in private facilities, compared with 10,377 in public facilities.[28] A national health facility assessment performed between November 2007 and July 2008 of all public EmOC facilities and private facilities providing obstetric services in the 64 districts of Bangladesh found that of 2376 facilities assessed, 316 had all CEmOC signal functions and 359 had all BEmOC signal functions.[29]

- India: A study in 2001 in four districts of West Bengal of 408 facilities found 17 CEmOC and 48 BEmOC facilities, and estimated that 26.2% of births occurred in EmOC.[30] A study in Gujarat in 2012-2013 of 159 facilities found 23 CEmOC and 3 BEmOC facilities, and estimated that among the facility births 24.1% occurred in CEmOC, 1.8% occurred in BEmOC, 46.8% occurred in less-than-BEmOC but with capability of C-section, and 27.3% occurred in less-than-BEmOC.[31] A needs assessment in 2010 in Karnataka found that of 466 facilities there were 136 CEmOC and 42 BEmOC facilities.[32]

- Nepal: A study in rural Nepal in 2018 found that only 1/16 facilities were capable of CEmOC, and at most 2 had all BEmOC signal functions.[33] A needs assessment of 157 facilities in Eastern, Western and Mid-western regions in 2000 found 5 BEmOC and 18 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 5.2% of births occurred in EmOC facilities.[19]

- Pakistan: A study of 2 districts in Pakistan (Haripur and Nowshera) in 2016 found that 22% of all births take place in public health facilities in both districts, of which 41% were conducted at health facilities that did not meet BEmOC criteria.[34] A needs assessment in 3 districts in Sindh Province in 1999 found 16 BEmOC and 13 CEmOC facilities, and estimated that 7.9% of births occurred in EmOC facilities.[35]

- Sri Lanka: A needs assessment of services provided in 1999 estimated that 72.9% of births occurred in CEmOC facilities, with 3.8% in BEmOC and 9.6% in BEmOC-2 (missing AVD and removal of retained products).[17]

- Thailand: A study in the five southernmost provinces of Thailand in 2004-2005 of 56 facilities found 12 CEmOC and and 43 BEmOC facilities, and estimated that 89.5% of births occurred in hospitals.[36]

- Timor-Leste: A national EmOC assessment in 2015 estimated that 47.8% of all expected live births occurred in facilities, and that 24.6% of birth occurred in EmOC facilities.[37] Out of 75 facilities they found 2 BEmOC and 6 CEmOC.

Latin America

- Bolivia: A needs assessment in 2003 found that 33% of births occurred in all facilities, and 24% occurred in EmOC and EmOC-1 facilities (performance of other signal functions but the absence of assisted vaginal delivery).[38] Out of 85 selected facilities in the study 7 were BEmOC-1, 20 were CEmOC, and 13 were CEmOC-1.

- El Salvador: A needs assessment in 2002 found that 46% of births occurred in facilities, and nearly all occurred in EmOC-1 facilities.[38] Out of 33 surveyed facilities 28 were CEmOC-1 (no AVD) and none were BEmOC

- Honduras: A needs assessment in 2002 found that 42% of births occurred in facilities, and 34% occurred in EmOC and EmOC-1 facilities (no AVD).[38] Out of 27 surveyed facilities 6 were CEmOC, 16 were CEmOC-1, and none were BEmOC.

- Nicaragua: A needs assessment of services provided in 1999-2000 in 112 facilities found 9 BEmOC-1 and 10 CEmOC-1 facilities (i.e. no AVD), and estimated that 44.5% of deliveries occurred in all facilities, and 28.7% occurred in EmOC facilities.[17]

- Peru: A needs assessment of services in 31 facilities in the six most northern provinces of Ayacucho in 1999-2000 found 2 CEmOC-1 (no AVD) facilities and no BEmOC, and estimated that 54.6% of births occurred in any facility and 25.9% occurred in the CEmOC facilities.[35]

North America

- USA: In the US in 2012, 1.36% of US births occurred outside a hospital - 66% of out-of-hospital births occurred at home, and another 29% occurred in a freestanding birthing center, with the remaining 5% of out-of-hospital births occurring in a clinic or doctor’s office or other location.[39]

Parameters

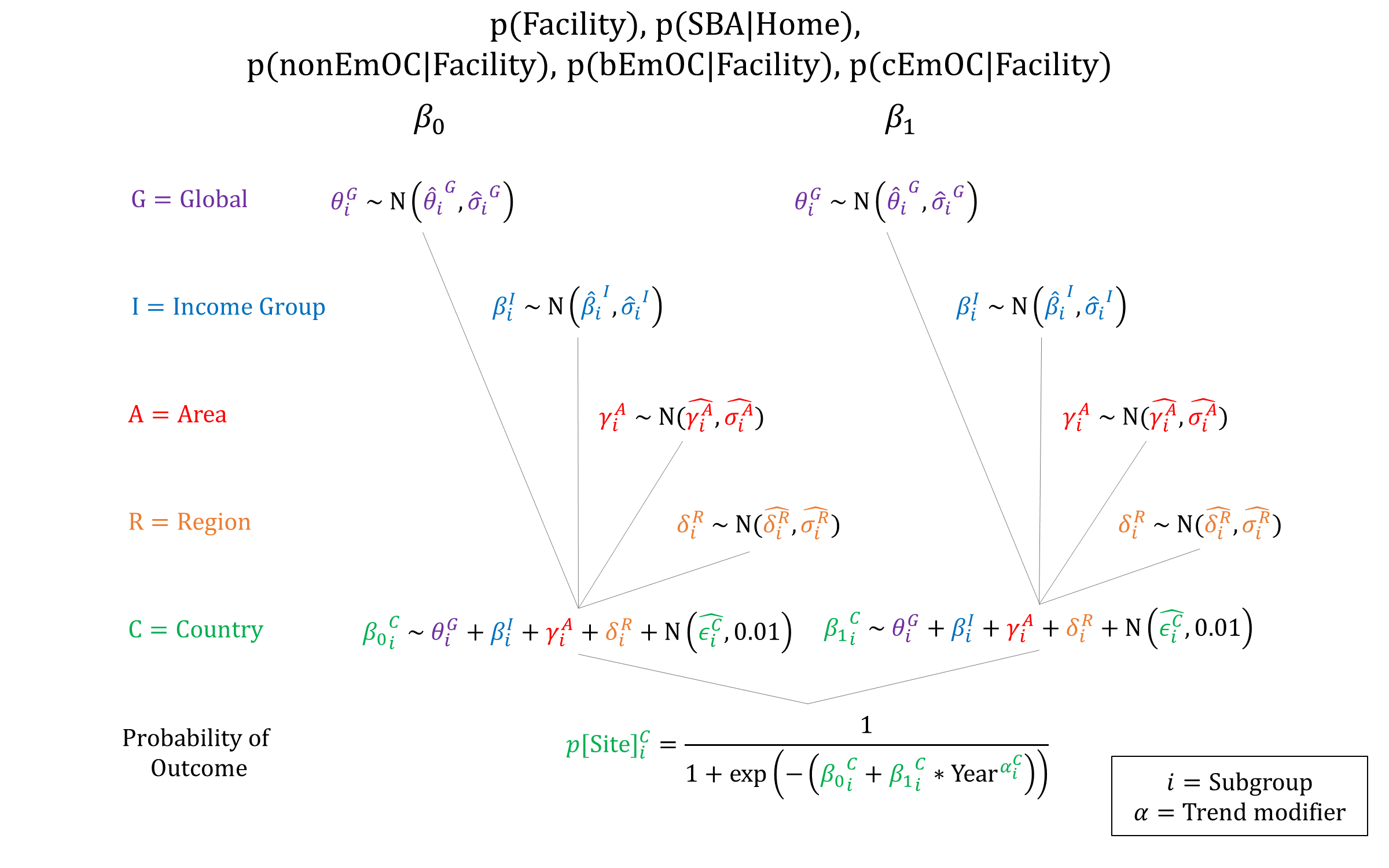

We used hierarchical logistic regression models to estimate priors for facility delivery and home-SBA based on the DHS data, and for EmOC status based on estimates from the literature. Modelled EmOC status probabilities are renormalized so that they sum to 1.0. While needs assessments often report the number of types of facilities, these counts do not account for the volume of deliveries by facility. When the percentage of deliveries by EmOC vs non-EmOC was reported, we used data on facility breakdown to set priors for the relative breakdown of deliveries by EmOC status. When only facility counts were available we assumed that CEmOCs have 2x the delivery volume of BEmOCs, and that BEmOCs have 2.5x the delivery volume of non-EmOCs when setting priors.

Priors

Model Implementation

At the time of delivery, the model simulates whether the woman will deliver at Home, Home-SBA, or at a Facility. Conditional on delivering at an institution, the type of facility is then drawn: non-EmOC, BEmOC, or CEmOC. Site-specific probabilities of preventive care and complication referral are then simulated.

References

- World Health Organization, UNFPA, UNICEF, AMDD. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547734_eng.pdf

- Global Health Observatory data repository. Births attended by skilled health personnel. Available at: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.SKILLEDBIRTHATTENDANTS?lang=en. Last updated: 2020-04-08

- UNFPA. Country programme document for Angola. DP/FPA/CPD/AGO/8. 2019. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/DP.FPA_.CPD_.AGO_.8_-_Angola_CPD_2020-2022_-_DRAFT_Final_-14Jun19.pdf

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Benin and Chad. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004; 86(1): 110-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.04.034

- Kouanda S, Ouédraogo AM, Ouédraogo GH, Sanon D, Belemviré S, Ouédraogo L. Emergency obstetric and neonatal care needs assessment: Results of the 2010 and 2014 surveys in Burkina Faso. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 135 Suppl 1: S11-S15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.008

- UNFPA. Country programme document for Burundi. DP/FPA/CPD/BDI/8. 2018. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/portal-document/DPFPACPDBDI8_EN.pdf

- UNFPA, AMDD. Making safe motherhood a reality in West Africa: Using indicators to programme for results. 2003. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/making-safe-motherhood-reality-west-africa

- UNFPA. Evaluation des besoins en soins obstetricaux et neonatals d’urgence dans trois provinces de la République Démocratique du Congo. 2012. Available at: https://drc.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/SONU_RAPPORT_ENQUETE_FINAL_DU_7_12_2012.pdf

- Admasu K, Haile-Mariam A, Bailey P. Indicators for availability, utilization, and quality of emergency obstetric care in Ethiopia, 2008. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 115(1): 101-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.07.010

- Fauveau V, UNFPA-AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, and The Gambia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007; 96(3): 233-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.12.004

- Bosomprah S, Tatem AJ, Dotse-Gborgbortsi W, Aboagye P, Matthews Z. Spatial distribution of emergency obstetric and newborn care services in Ghana: using the evidence to plan interventions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 132(1): 130-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.11.004

- Baguiya A, Meda IB, Millogo T, Kourouma M, Mouniri H, Kouanda S. Availability and utilization of obstetric and newborn care in Guinea: a national needs assessment. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 135 Suppl 1: S2-S6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.09.004

- National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development (NCAPD), Ministry of Medical Services (MOMS), Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (MOPHS), Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), ICF Macro. 2011. Kenya Service Provision Assessment Survey 2010. Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA17/SPA17.pdf

- Pearson L, Shoo R. Availability and use of emergency obstetric services: Kenya, Rwanda, Southern Sudan, and Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005; 88(2): 208-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.09.027

- Kongnyuy EJ, Hofman J, Mlava G, Mhango C, van den Broek N. Availability, utilisation and quality of basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care services in Malawi. Matern Child Health J 2009; 13(5): 687-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0380-y

- Otchere SA, Kayo A. The challenges of improving emergency obstetric care in two rural districts in Mali. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007; 99(2): 173-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.004

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Morocco, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003; 80(2): 222-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00390-9

- Augusto O, Keyes EE, Madede T, et al. Progress in Mozambique: Changes in the availability, use, and quality of emergency obstetric and newborn care between 2007 and 2012. PLoS One 2018; 13(7): e0199883. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199883

- Bailey PE, Paxton A. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002; 76(3): 299-305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00592-6

- Ministry of Health and Social Services, Namibia. Report on emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessment. 2016. Available at: https://cmnh.lstmed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/content/centre-news-articles/attachments/203264-Full%20report_Namibia%20EmONC%20Assessment.pdf

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Niger, Rwanda and Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003; 83(1): 112-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00187-5

- Kabo I, Orobaton N, Abdulkarim M, et al. Strengthening and monitoring health system’s capacity to improve availability, utilization and quality of emergency obstetric care in northern Nigeria. PLoS One 2019; 14(2): e0211858. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211858

- Saidu R, August EM, Alio AP, Salihu HM, Saka MJ, Jimoh AAG. An assessment of essential maternal health services in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2013; 17(1): 41-8. PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24069733/

- Jones SA, Gopalakrishnan S, Ameh CA, White S, van den Broek NR. ‘Women and babies are dying but not of Ebola’: the effect of the Ebola virus epidemic on the availability, uptake and outcomes of maternal and newborn health services in Sierra Leone. BMJ Glob Health 2016; 1(3): e000065. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000065

- Oyerinde K, Harding Y, Amara P, Kanu R, Shoo R, Daoh K. The status of maternal and newborn care services in Sierra Leone 8 years after ceasefire. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 114(2): 168-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.05.006

- Fakih B, Nofly AAS, Ali AO, et al. The status of maternal and newborn health care services in Zanzibar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016; 16(1): 134. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0928-6

- Young-Mi K, Zainullah P, Mungia J, Tappis H, Bartlett L, Zaka N. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric and neonatal care services in Afghanistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012; 116(3): 192-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.017

- Sikder SS, Labrique AB, Ali H, et al. Availability of emergency obstetric care (EmOC) among public and private health facilities in rural northwest Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1405-2

- Alam B, Mridha MK, Biswas TK, Roy L, Rahman M, Chowdhury ME. Coverage of emergency obstetric care and availability of services in public and private health facilities in Bangladesh. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015; 131(1): 63-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.041

- Biswas AB, Das DK, Misra R, Roy RN, Ghosh D, Mitra K. Availability and use of emergency obstetric care services in four districts of West Bengal, India. J Health Popul Nutr 2005; 23(3): 266-74. PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16262024/

- Salazar M, Vora K, De Costa A. The dominance of the private sector in the provision of emergency obstetric care: studies from Gujarat, India. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 225. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1473-8

- Mony PK, Krishnamurthy J, Thomas A, et al. Availability and distribution of emergency obstetric care services in Karnataka State, South India: access and equity considerations. PLoS One 2013; 8(5): e64126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064126

- Banstola A, Simkhada P, van Teijlingen E, et al. The availability of emergency obstetric care in birthing centres in rural Nepal: a cross-sectional survey. Matern Child Health J 2020; 24(6): 806-816. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02832-2

- Brückmann P, Hashmi A, Kuch M, Kuhnt J, Monfared I, Vollmer S. Public provision of emergency obstetric care: a case study in two districts of Pakistan. BMJ Open 2019; 9(5): e027187. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027187

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Averting Maternal Death and Disability. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Pakistan, Peru and Vietnam. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002; 78(3): 275-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00190-x

- Liabsuetrakul T, Peeyananjarassri K, Tassee S, Sanguanchua S, Chaipinitpan S. Emergency obstetric care in the southernmost provinces of Thailand. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19(4): 250-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm023

- Ministry of Health, Timor-Leste. Emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessment - Timor-Leste 2015. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/timor-leste/emergency-obstetric-and-newborn-care-needs-assessment-timor-leste-2015

- Bailey P, AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Bolivia, El Salvador and Honduras. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005; 89(2): 221-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.12.045

- MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Declercq E. Trends in out-of-hospital births in the United States, 1990-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2014; 144: 1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db144.pdf

GMatH (Global Maternal Health) Model - Last updated: 28 November 2022

© Copyright 2020-2022 Zachary J. Ward

zward@hsph.harvard.edu