Transportation

Model Inputs \(\rightarrow\) Health System Parameters \(\rightarrow\) Transportation

Overview

Once a complication has been recognized/referred, the woman needs some way to get to a facility in time to receive care. A systematic review found three main themes related to this ‘second delay’: availability of transportation infrastructure, distance from the health facility, and lack of finance for transportation.[1] These barriers resulted in delays on the way to a health facility even if the decision to seek care was made in a timely manner, with the majority of delays due to a shortage of vehicles, poor road infrastructure, and shortage of ambulances.[1] This probability in the model encapsulates both the availability and timeliness of transport.

Data

A systematic review found it was usually difficult for women with lower household income to afford transportation fees, and distance from a health facility was also found to a major barrier.[1] However, a study in Rwanda found that lack of transportation and the quality of roads were not identified as major barriers to care, with only 0.8% of maternal near misses and deaths considered preventable due to difficulty reaching a tertiary care facility.[2] In India, all women in the Coverage Evaluation Survey 2009-10 who had institutional deliveries were asked about the mode of transport used to reach the health facility and the costs incurred.[3] Around 6.5% of women used an ambulance and 30.9% used a jeep/car to reach the health facility, while 7.5% travelled by motorcycle or scooter. However, many women reportedly used other modes of transport such as bus/train (6.6%), and tempo/auto/tractor (34.1%). Nearly 5% of women reportedly reached the health facility on foot. Women in rural areas travelled an average of 11.2 km, taking an average time of 39.2 minutes, compared to those in urban areas who travelled 4.9 km, taking 24.3 minutes. The mean transport cost was 192 Rupees (Rural: 243; Urban: 140), although about 21% of women did not incur any transportation cost to reach the facility. Overall, only 10.4% of women who delivered at home said they did not deliver at an institution because it was too far, or that they lacked transport. However, the availability of emergency transportation for complications may be quite different than for planned deliveries in a facility. According to the District Level Household Survey (2007-08), only 55% of villages had referral services for complications.[4] Successfully transferring a woman from a site of complication to a definite level of care requires stabilization and transfer protocols, communications technology, and transportation and cost arrangements, with reliable transportation often a missing link to timely, accessible, and affordable emergency care.[5]

Transport availability can also be lacking for women who are already at a facility. In a review of public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India, it was found that there were only 10 ambulances available for 15 facilities, compared to the 19 required by the Indian Public Health Standards.[5] Furthermore, only 8 of 15 facilities had ambulances in working order with at least 1 driver and funds available for fuel and maintenance. No facility was offering regular, round-the-clock referral transport, including the district hospital, and it was estimated that 27% of maternal deaths occurred en route to a facility, highlighting the importance of timely transportation.[5] Another study by Chaturvedi (2014) found that the average inter-facility travel time was 1.25 hours,[6] while Sabde (2014) found that the median time needed to reach a facility after making the decision to seek care was nearly 2 hours, with only 12% of women reaching a facility within 1 hour.[7] However, improvements are being made in some areas. A study of the National Ambulance Service (NAS) in Haryana found that once a call was made, the NAS ambulance took an average of 18.8 min to reach the site of emergency and 21.7 min to transport the patient to the hospital from site of emergency.[8] In nearly 90% of the cases, a NAS ambulance reached the site of emergency within 30 min of call, while in 80% of the cases the patient reached a facility within 1 hour of calling. A 2008 study in Sierra Leone found that only 10% of health facilities had an ambulance, while 22% had an unequipped ambulance.[9] A study in the Lake and Western zones in Tanzania found that 25% of hospitals and health centers reported that they were not able to access an ambulance.[10]

Parameters

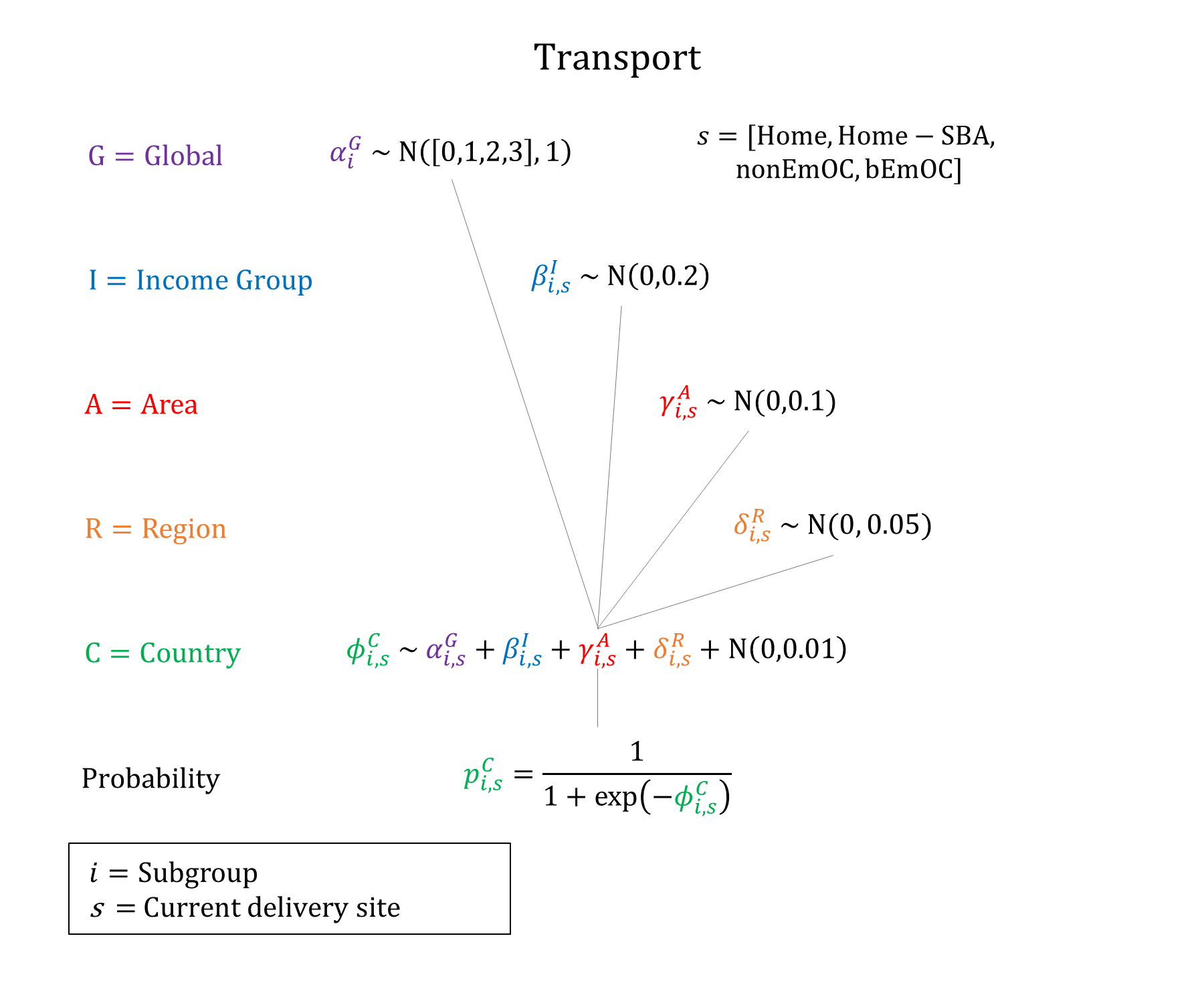

We used hierarchical logistic regression models to model the probability of timely transportation. We assume that women with higher education are more likely to have the resources to obtain transport, and that women in urban areas have shorter distances to travel. We also assume that transport probabilities increase with more advanced delivery site. These constraints were enforced when sampling probabilities in the model.

Priors

Model Implementation

Conditional on successful recognition and the need for referral, the probabilities of successful (and timely) transport are simulated based on a woman’s current site of delivery and subgroup.

References

- Geleto A, Chojenta C, Musa A, Loxton D. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of literature. Syst Rev 2018; 7(1): 183. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0842-2

- Benimana C, Small M, Rulisa S. Preventability of maternal near miss and mortality in Rwanda: A case series from the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK). PLoS One 2018; 13(6): e0195711. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195711

- India Coverage Evaluation Survey 2009-2010. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (India), ORG Centre for Social Research (ORG CSR), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Available: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/india-coverage-evaluation-survey-2009-2010.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. India District Level Household Survey 2007-2008. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. Available: http://rchiips.org/PRCH-3.html.

- Raj SS, Manthri S, Sahoo PK. Emergency referral transport for maternal complication: lessons from the community based maternal deaths audits in Unnao district, Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015; 4(2): 99-106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.14

- Chaturvedi S, Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. Quality of obstetric referral services in India’s JSY cash transfer programme for institutional births: a study from Madhya Pradesh province. PLoS One 2014; 9(5): e96773. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096773

- Sabde Y, De Costa A, Diwan V. A spatial analysis to study access to emergency obstetric transport services under the public private “Janani Express Yojana” program in two districts of Madhya Pradesh, India. Reprod Health 2014; 11: 57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-57

- Prinja S, Jeet G, Kaur M, Aggarwal AK, Manchanda N, Kumar R. Impact of referral transport system on institutional deliveries in Haryana, India. Indian J Med Res 2014; 139(6): 883-91. PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25109723/

- Oyerinde K, Harding Y, Amara P, Kanu R, Shoo R, Daoh K. The status of maternal and newborn care services in Sierra Leone 8 years after ceasefire. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 114(2): 168-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.05.006

- Maswanya E, Muganyizi P, Kilima S, Mogella D, Massaga J. Practice of emergency obstetric care signal functions and reasons for non-provision among health centers and hospitals in Lake and Western zones of Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18(1): 944. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3685-6

GMatH (Global Maternal Health) Model - Last updated: 28 November 2022

© Copyright 2020-2022 Zachary J. Ward

zward@hsph.harvard.edu