Assisted Delivery

Model Inputs \(\rightarrow\) Clinical Interventions \(\rightarrow\) Assisted Delivery

Overview

Most women give birth spontaneously, but some need assistance during the second stage of labour with instruments such as obstetric forceps or vacuum, especially in the case of obstructed or prolonged labor. A Cochrane review found that overall, forceps or metal cup appear to be the most effective at achieving a vaginal birth, but with increased risk of maternal trauma with forceps and neonatal trauma with the metal cup.[1] Over the past two decades authorities have declared vacuum extraction the method of choice in modern obstetric practice due to improved safety for the fetus and less likelihood of maternal morbidity.[2] The risks of failed delivery and trade-offs between risks of maternal and neonatal trauma thus need to be considered when choosing an instrument.

In the event that labor cannot be resolved by manipulation (to reposition the fetus) or instrumentation, Caesarean section may be required. Caesarean section (C-section) is a common abdominal operation for surgical delivery of a baby and the placenta, with techniques varying depending on the clinical situation and surgeon preferences.[3] However, C-sections require effective anesthesia which can be regional (epidural or spinal) or a general anesthetic.[4]

Data

The rates of instrumental vaginal births range from 5% to 20% of births in high-income countries, with less information about the incidence in low-income countries.[5] In general, assisted vaginal delivery (AVD) is more common in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[2] A limited review of EmOC signal functions in 2006 found that AVD was generally the signal function least likely to have been performed.[6] Other studies in sub-Saharan Africa also find that AVD was the signal function most often missing in health facilities.[7,8] In Latin America, availability of AVD may be even lower - previous studies reported it to be completely missing for facilities in Nicaragua,[9] and uncommon in Peru and no longer part of the pre-service training curriculum at some of the country’s leading medical schools.[10] A review of AVD found that it is more likely to be performed in hospitals than in health centres and clinics, and the top reported reason for non-performance was equipment-related, followed by lack of staff training.[2] Most countries surveyed appeared to show a preference for vacuum extraction over forceps, especially at non-hospitals, which may reflect the global transition in instrument choice and a consensus that forceps is more difficult to use and less versatile.[2]

We identified multiple studies that examined the efficacy of treating obstructed labor on reducing maternal mortality rates.[11,12,13,14] The efficacy of assisted delivery for obstructed labor is high - for example, Yarrow 2004 reported a 94.1% success rate when using vacuum-assisted deliveries, and of the nine failed vacuum deliveries, four were subsequently delivered by forceps and five by cesarean section, with no maternal mortality reported.[15] AVD is thus sometimes first attempted, with a c-section performed if needed. A multi-country study in sub-Saharan Africa found that obstructed labor accounted for 31.3% of all c-sections, followed by malpresentation (18.3%).[16] A WHO Global survey in 2004-2008 found that operative vaginal deliveries accounted for only 2.6% of deliveries, compared to nearly 25% of deliveries by c-section with indications, suggesting that c-sections are far more commonly used than AVD.[17] We include these estimates of operative vaginal deliveries as calibration targets in the model.

Parameters

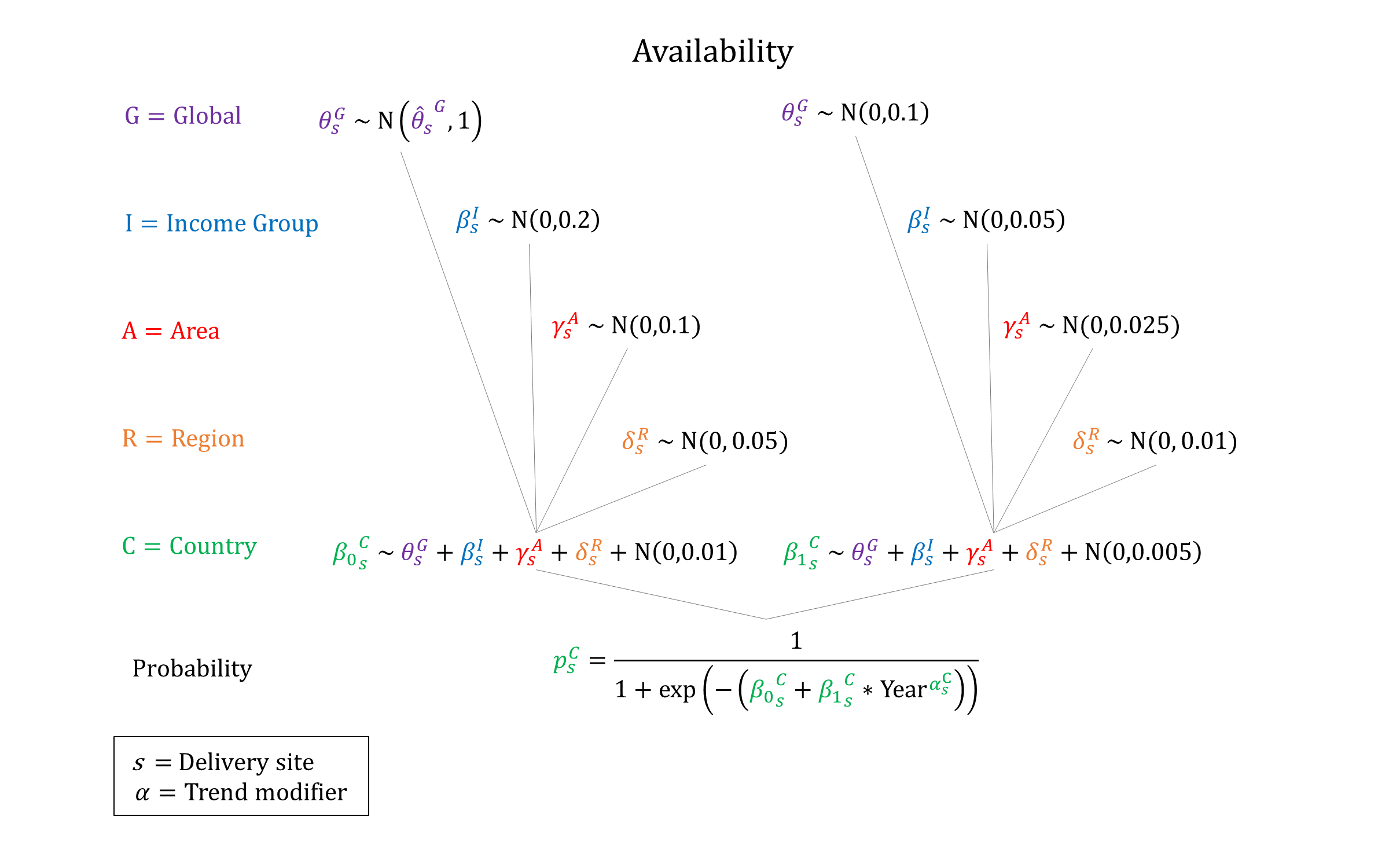

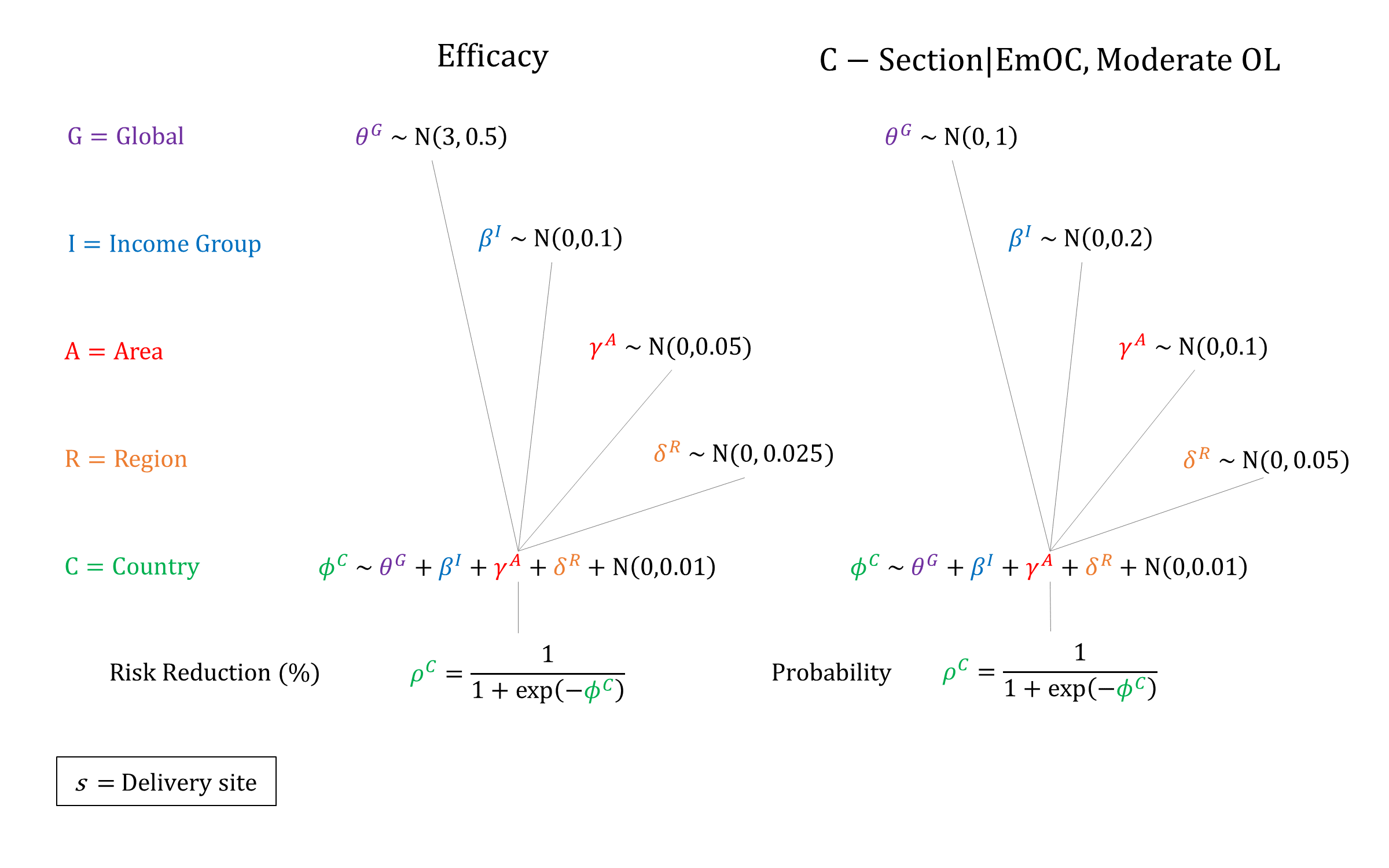

For women with obstructed labour, we model the availability and efficacy of assisted delivery, conditional on delivery site. We assume that the availability of treatment increases by site and income group, and that treatment is not available at home. We assume that treatment availability increases over time and so constrain the year coefficient to be non-negative when sampling. We assume that ‘severe’ OL requires c-section and can only be treated at CEmOC facilities, while ‘moderate’ OL can be treated with AVD if available. However, given the preference for c-section over AVD in many cases, we simulate a probability of c-section instead of AVD for women with moderate OL at EmOC as well. We assume that the efficacy of treatment is non-differential by severity (moderate/severe) or mode (AVD/c-section), and apply the same risk reduction for all mortality and morbidity outcomes. We set priors centered around 95% efficacy for risk reduction based on the empirical data.

Priors

Model Implementation

Conditional on the delivery site we simulate the probabilities that treatment will be available and the efficacy of treatment on obstructed labour outcomes, accounting for quality of care.

References

- O’Mahony F, Hofmeyr GJ, Menon V. Choice of instruments for assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 11: CD005455. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd005455.pub2

- Bailey PE, van Roosmalen J, Mola G, Evans C, de Bernis L, Dao B. Assisted vaginal delivery in low and middle income countries: an overview. BJOG 2017; 124: 1335–1344. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14477

- Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S, Grivell RM. Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 7: CD004732. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004732.pub3

- Afolabi BB, Lesi FE. Regional versus general anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD004350. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004350.pub3

- Majoko F, Gardener G. Trial of instrumental delivery in theatre versus immediate caesarean section for anticipated difficult assisted births. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD005545. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd005545.pub3

- Bailey P, Paxton A, Lobis S, Fry D. The availability of life-saving obstetric services in developing countries: an in-depth look at the signal functions for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2006; 93(3): 285–91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.01.028

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Benin and Chad. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004; 86(1): 110-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.04.034

- Pearson L, Shoo R. Availability and use of emergency obstetric services: Kenya, Rwanda, Southern Sudan, and Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005; 88(2): 208-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.09.027

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Morocco, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003; 80(2): 222-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00390-9

- AMDD Working Group on Indicators. Averting Maternal Death and Disability. Program Note: Using UN process indicators to assess needs in emergency obstetric services: Pakistan, Peru and Vietnam. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002; 78(3): 275-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00190-x

- Schuitemaker N, van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, van Dongen P, van Geijn H, Gravenhost JB. Maternal mortality after cesarean section in The Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997; 76(4): 332-334. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.1997.tb07987.x

- Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ 2005; 331(7525): 1107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1107

- Pasupathy D, Wood AM, Pell JP, Fleming M, Smith GCS. Time trend in the risk of delivery-related perinatal and neonatal death associated with breech presentation at term. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38(2): 490-498. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn225

- Ameh CA, Weeks AD. The role of instrumental vaginal delivery in low resource settings. BJOG 2009; 116(S1): 22-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02331.x

- Yarrow C, Benoit G, Klein MC. Outcomes after vacuum-assisted deliveries. Births attended by community family practitioners. Can Fam Physician 2004; 50: 1109-14. Available at: https://www.cfp.ca/content/50/8/1109.long

- Chu K, Cortier H, Maldonado F, Mashant T, Ford N, Trelles M. Cesarean section rates and indications in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country study from Medecins sans Frontieres. PLoS One 2012; 7(9): e44484. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044484

- Souza JP, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Med 2010; 8: 71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-71

GMatH (Global Maternal Health) Model - Last updated: 28 November 2022

© Copyright 2020-2022 Zachary J. Ward

zward@hsph.harvard.edu